“… there is a density to time.”

(30, “The Passes”)

With bookmark in place, I was tentative about my wrist adjustments while reading Andrew Bertaina’s THE BODY IS A TEMPORARY GATHERING PLACE, knowing I was nearly a year late in appreciating the unbroken spine and fresh indention of the author’s note to myself. By the time I started reading “BODY” this January, the offer to read and wrangle some semblance of a review was some eleven months in the past. As Bertaina writes in his fifth essay, “Time moves on like the obscenity that it is.” (37, “Time Passes”) I felt like an asshole watching it go, but not only that, knew as it gathered speed against me that I was someone whose own pathological negligence had, once again, tripped her up. The feeling of deliverable purpose had expired. I’d failed in my delivery of a promised product and in that failure, tripped ungallantly out of the online indie literature community via X debacles, my account so aflame with malevolent feeling (some, rightfully felt) that I’ve exiled myself to a recalcitrant blog and limited social media access.

I fumbled this opportunity and want to offer my deep, not-enough apology to Mr. Bertaina. I gained a job in the midst of writing book reviews this Spring. This 9-5 existence has placed limitations around my time as reader. Instead of pouting like a white girl, I hope that I’m respectfully reviewing books that shed light on health writing in the subtle and extreme ways sophisticated narratives layered with recurrent health complaints can afford the weary reader in these times of strife. When an author complains, the good reader pays attention. When the author complains a second or third time, it’s called a theme. By the fourth, it’s something as overarching as writer’s impetus for writing. By the fifth, it’s their reason for being here, in the room, telling us to read, in the first place.

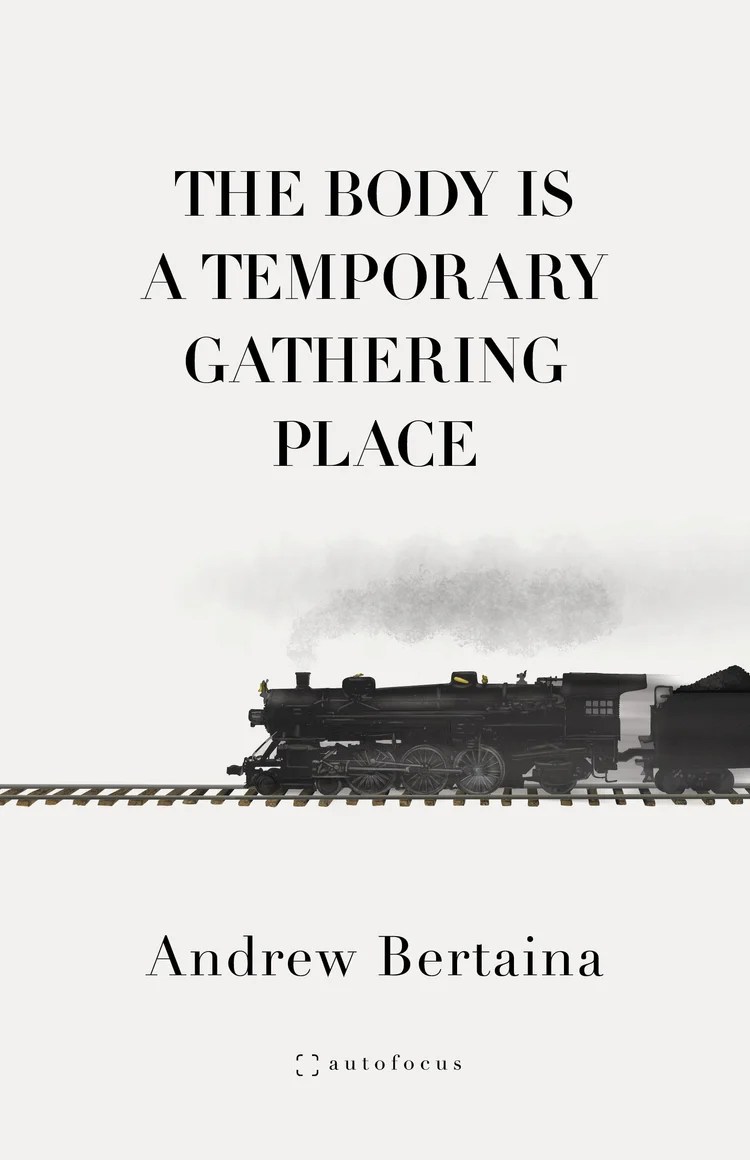

In one of Bertaina’s essays, “On Trains”, a train—yes, I’m this tired—features prominently as lucid vehicle for navigating the pitted terrains of Bertaina’s mental state at the moments—in my romantic guestimations, probably weeks—it took to write this piece. Trains are quiet and semi-slow and the essay rears back on itself lazily. Its long ride begs into consideration this: maybe we should go ahead and call him a genius. Utilizing something as tried as trains to anchor narrative into an easy gallop and getting away with it, in this economy, when the socioeconomics of this kind of travel are held to the light for inspection—rich? bored? the privilege is there but maybe we forgive him?—makes me wonder what Bertaina was like in writings workshops. I’m a little jealous. That jealousy’s good, as I’ll tend towards criticism later in this review. By this point in the collection, I liked Bertaina as a person, not a narrator.

He is hopeful for the wide-open spaces of travel and wants badly to embark on an affair that he spends the majority of page 57 scripting towards impetus. “Marriage is not clean,” (54), leads us through a chronology that Bertaina breaks in half in hopes of telling a love story with a certain appetite for fragmentation. Which, I guess, is to be expected when retelling how you met your ex-wife. A wife met abroad is a dangerous subject to tell dinner party guests. We are his dinner party guests, and the judgement I felt was confused, probably so deeply irrational I’d blush if I tried, stuttering, amidst strangers or friends alike, to tell you why I felt he should keep to himself. I am irrational. Realizing this while copying this sentence over to Word from an earlier draft of this review feels silly, also profound.

Bertaina’s ability to inspire this kind of jealousy in a 35-year-old woman speaks to the strength of his persuasive writing abilities and unzips gendered notions around who could and should and would delight in reading him. “There is no sexy way to describe sitting for an hour a day, trying to learn to identify thoughts and emotions as they arise, to slowly tend to whatever is left of your loving heart.” (169, “The Leopard”).

Despite my punky-feminine approaches to picking books, I enjoyed Bertaina’s attempts at including one of the 21st century’s most polarizing characters. Don Draper gets screentime in “The Leopard”, (“The world is not interested in my happiness.” (164) nearly to a point where I questioned its purpose, however enjoyable it was, so much of it, too, providing transport to Sunday evenings in 2012 when the boy I liked planned time and means around airings so fraught with aesthetic it made grown men cry. I watched myself watch Mad Men through Bertaina’s eyes and thanked him for the cereal bowl. Nostalgia’s at the bottom, and good, sweet Don is resurrected for a moment on that California hill and given new purpose.“In Mad Men, Don’s crisis doesn’t lead to any meaningful change… [i]s this all there is? Just the flecks of light on water?” (168-169). If it works is beside the point. Bertaina’s provides us with pleasure, and that’s enough.

If we measure greatness more often than not by size, then I’ll stray left in my argument that Bertaina’s purpose for “On Being 35” was about vanity, sweetly enough, without the impulse for counting calendar years or riffling through a billfold of beer pong photos and the formal posings of late 20’s neo-adolescence. I’d expected a show of incidents the author led us, donkey though, ambling up to this great date, but instead, found a brief essay informed by millennial navel-grazing. It was the kind I knew as familiarly as my own relentless, oftentimes hopeless search for self-parody. My own writing suffers from it badly enough to have fostered groups of enemies because of my careless narcissism. Bertaina, however, saves it just in time by a scene I’ll remember for the precarious way it reveals the uncertain soul of its author. “I am a stray elbow, a portion of the upper ear, the remains of pinkie finger, lying in a room off to the side, signifying nothing but what might have been.” (91) The revelation is ancient, set against the indecency of Italian daylight, in the The Galleria dell’Accademia. He, a self-described auteur about people-pleasing and showmanship (and about the hoity-toity essentials that make up the upper crust setting of cultural czars, conversation, and charcuterie) elegantly calls himself out on page 88 as a bit of a liar. All for the aesthetic, of course, and his reasoning, like any good fire sign, is pure and filled with the gentle heat of harder work still… but his second mention of elementary school math is telling. In this essay, Bertaina’s an adult, breathing—still—with adolescent nose, feels it necessary to comment on his school performance as way of justifying himself to the reader.

It takes art and the hollow air of a museum to bend young Bertaina’s ego into a bow:

“These false constructions are what makes being a human being livable.” (46, “Departures”)

David, his clear pallor of youth, the marble skin of his neck.

Bertaina standing below him.

David’s looking left.

Bertaina due North.

David, a little lazy-hungry for an expectation he’s either just glimpsed or feigns slight chagrin towards.

Bertaina, smaller, and comprised of organ, faulty to his thumb tips and heavy for five minutes beneath the erosion of self-replacement*.

“I’m careful as I walk, such a fragile thing, a knee, a body, a life.” (172, “The Leopard”).

The psychological circumstance of realizing one’s inferiority belies knowing oneself in the mirror in the morning for something more painful, still. I sympathized with the deep humidity of emotion that Bertaina (young, still green, it feels, in this particular piece) is on the—to recycle words for the sake of the late-night review—precarious route towards locating. Above the jaw and under the eye, there’s a small pock of ego for the taking. Art steals things from us. The reader plays witness to Bertaina’s theft and smiles sadly.

Bertaina’s primarily macho leanings are glued against a composite of time spent with his children: purposeful parts of the house, necessary places, making daily actions towards goals like bathing and bedtime, which contains a sweet dichotomy. Bertaina suddenly shows up as the man with the bar of soap and rubber duckie and the abandoned work in the next room, and we forgive him for everything. Taking care like that feels holy. At least four of the essays—“The Thin Ribbon”, “On Showering and Mortality”, “This Essay is About Everything”, “Home Burial”—end in this way. Choosing to end four of his essays with childcare hints at intention that isn’t as obvious as you’d expect, but obvious enough to inspire a productive curiosity around a man who may or may not be depressed. If he were a woman, we’d ignore these scenes for natural. “But forever is a long time, and we were reading The Secret Garden in a matter of minutes.” (146, “Home Burial”) Since he’s a man, we grow fonder of Bertaina for these actions, although, I have questions. To criticize someone else’s narrative parenting style when I myself have no children and plan for a life lived separately from the mainstream, seems wildly inappropriate of me. And to suggest more edits feels like libel.

I do this for a greater purpose that has to do with mental health-informed artistry, and how we write around it, and how, by level of sentence-to-sentence, it’s spectral to our output, shows up in the damnedest ways.

Bertaina’s mental health deteriorates throughout the series of essays and was alarming to witness, fresh, sitting on my Saturday like the crudest of sketches (“SAD”, figure 1: girl treats existence like potato chip crumbs) due to my own fresh hell of post-suicidal ideations. Reading a depressed person while equally depressed (can I equate the two? Is that also harmful?) is, for lack of any better ways of phrasing it, a meta experience. Dealing for several essays with what I (no expert, just fellow sufferer) would equate with acute depression, while going seventy-five-percent-or-seeming stag in rearing two children whose main lines in the book deal in death tones is (!) disturbing material to find yourself through. What kind of parent writes about their child’s evening meltdown over the afterlife and what writer includes the harsh, sparse advice he bestows upon that small, weeping figure? Look to the stars, honey, there’s nothing to look forward to and that in itself is a way forwards… I made that up, I guess it’s what I’d say to a child if I didn’t have some faith in our afters. I write it only to grapple with an empathy that took me several days to heal in place for Bertaina. I’m trying too hard to find my own actions in Bertaina’s and that’s a classic example of reading the text wrong.

I wonder whether mental health has, as usual, ruined entire evenings of childhood development pressure-points Bertaina’s self-tasked himself with handling without the warm glue of wife. I’d like to suggest that Bertaina just doesn’t give a shit, but I’d be lazy and siding with the customary stupidness that has, on occasion, overtaken me when seeking any insight at all. I’m a regular joe reader, and maybe I should shut up now. Give me one more paragraph, and I promise that I will.

He so obviously cares. The paragraphs he’s elected to use towards describing parental duties are fractals of moments he’s generous enough to share with us. We pay witness to Bertaina parenting through a crisis that’s so deeply blasted with the great horror of living again, another next day. “Certainly, consciousness must have resided there, what a religious person might call a soul… [w]e know so little about the lives that are not our own.” (146, “Home Burial”) When he speaks about death with his children, it feels… what? They have to know.

“Most days they seemed not to notice the sadness that threatened to engulf me. I had to remind them I was miserable.

Daddy is sad.

Is that why you were being mean today?” (161, “The Leopard”)

Bertaina does his sadness in ways that feels—I’m stupid, please don’t think I’m attempting diagnosis—unaware of itself. These essays are lapses in thought, and every essay is noticeably moody. Has the depressive parent been done before (yes) and in this way (I’m not sure)? “Who knew that the garden would last longer than the marriage?” (157, “Home Burial”)

Oftentimes, I have noticed writers working their way towards breeching family life in the midst of their self-revelry by making bold attempts at writing a living circus into their narratives. Childrearing, but glorified. Childrearing, but edited to such pristine shine that there is no fault left to consider. It’s hard not to romanticize our children. Forgive these writers. This pretense is appreciated by readers because reading about a favorite writer being a bad parent is not only terrible PR but grounds for the reader having to do something about it. Maybe I’ve missed something, here, and maybe, too, there’s some intentionality behind Bertaina’s children’s inclusion that—without proper insight into the book’s publishing history—I lack the proper supplies to consider.

“And though I agree we are insignificant, like many other thinkers, I think that makes our brevity meaningful.”

(36, “The Passes”)

Bertaina’s heavy flirtation with death and the immediate after is something I can’t uncurl my shoulders around, or overlook, but fear may be too heady of an undertaking to explore further in this weird review. I’ll ask one question and leave you with a quote, ride away on my broomstick that’s make is 2018, dark navy, and past the point of maintenance at this strange, scary, interval in human history. Does Death have a place in the nursery?

Leave a comment