“The children understood. They saw light-years / past my matted fur, my incisors, the bad / press. Past caricatures that would frighten / shadows out of alleyways. They mistook me / for El Ratoncito Pérez, begged for mercy / on my behalf, and given the chance / I’d have squatted in front of his magic door / until their teeth fell out, prowled / the world for treasures to tuck under / their pillows.” (94)

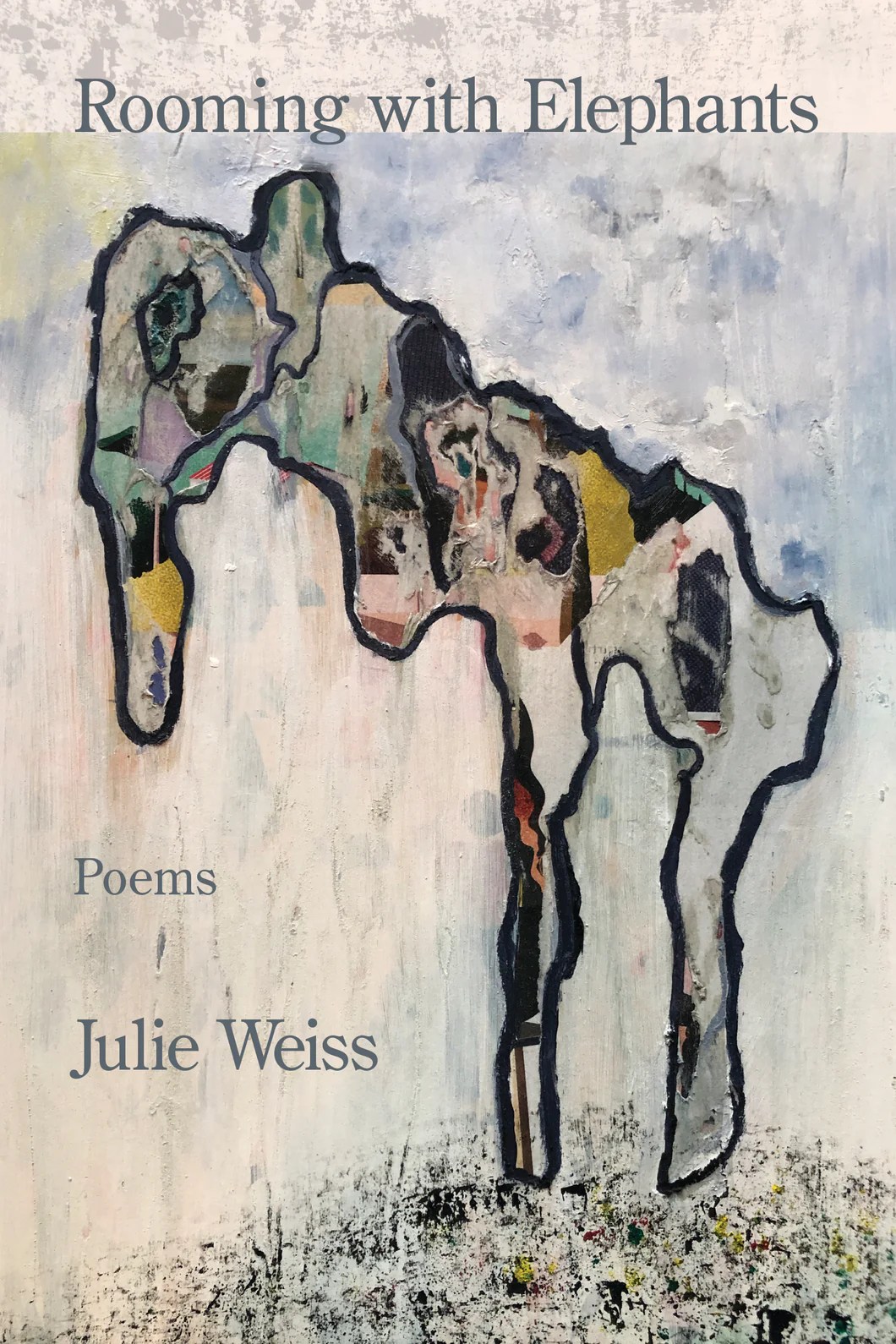

Rearing children against our present-day apocalyptic landscape serves as Julie Weiss’s dominant poetic engine in her collection ROOMING WITH ELEPHANTS. Mothers have the troubled task of deduction. “In the room’s maddening / orbit, I reach for them, but they’ve already / turned back to their cartoons, blind / to the years melting off their mother’s body. / Deaf to my hormones, ticking.”(106) Hosting games and erecting, or, in effect, plunging this decade’s awful quiet of bated-breath-living with the sweet towers of make-believe is a necessary desperation for modern mothering. Maybe these twilight teepees and liars hopes will keep the news muted long enough for the children to laugh at least once. “I plead: let’s keep reading / kiss their foreheads, which are creased / into a question the living can’t punctuate / and the dead won’t answer except in jest, / trumpeting the elephant into the room.” (21) Weiss’s knowledge of social warfare sits in motherhood’s lap. “My children splash each other in the tub. Guns are blooming in sweet American soil.” (32) She offers us no solution. Instead, she lends us snatches of violent American example to bevy her point more ferociously. We’re either killers or victims and the child’s eyes are large enough to absorb both and without explanation, what happens to them? “How do you map out death for a child?” (69) The chronology of Covid is foundational to this collection, serving as a tender paradigm for modern tragedies in the past five years. I even made a small–though, I promise, emotionally arousing–list of her poetry that dealt exclusively with such: “Dining in the Time of Covid” (25), “When the Virus Goes Away” (26-27), “The Day I Don’t Tell My Children About the Capitol Attack” (28). I wonder, too, about her poetry that takes aims toward the global? Should we treat it as something like a relieving juxtaposition for our previous world? “I’d rinse off my mouth when I became a mother.” (48) Should we ignore her own youth or view it as an attempt at biography? “I’ve become so good at bewailing the untamed gray, the trampled years around my eyes…” (70) What makes the mother’s own history a necessary presence in her children’s? “In my bleakest moments, / they materialize, all those spirits / stampeding through our home, / encircling us.” (108) The elephant’s decapitation and Weiss’s generous attempts to gormandize its body whole feels necessary to comment on. I’m sitting here, reviewing the elephant’s ecological purpose in our chain-of-command. As an umbrella species, they serve as pioneers for their natural habitats, including but not limited to clearing paths through jungles for their neighboring species, providing instances of seed dispersal throughout the animal kingdom, and regulating their environments through their gentle destructions by breaking ground for newer variety of vegetation to emerge.[1] In light of this collection’s visceral politics, what makes the elephant worthy to eat?

Leave a comment