There’s something to be said for the narrative arc that begins with a runaway, as we’ve all felt that urge to upend reality for a better existence. Culture inundates us with alternatives that promise happy completes, and it’s difficult to resist the flash-in-the-pan quality of lives set to shimmer. Social media preys hungrily on those of us quartered in unhappy realities, feels, at times, like a plague on the senses, which is why detoxes exist and apps are deleted, hidden so fervently for half a week in order for us to right ourselves again, shake the pearly screen luster from our hair and clothes and eyes, and experience the mundane, sans the digital celebration of lives bent in pursuit of Aesthetic. Everything feels like a trap even when it’s not, even when, for the large part, it’s the normal human experience: pain, loss, rinse and repeat, the recipe’s always been clear but the messaging varies these days thanks to generational divide and compacted trauma. Reality’s upsetting. Not only do we not get what we want, but we’re tasked with burdens–I tend towards calling them ‘crosses’–that feel like some strain of cosmic discipline.

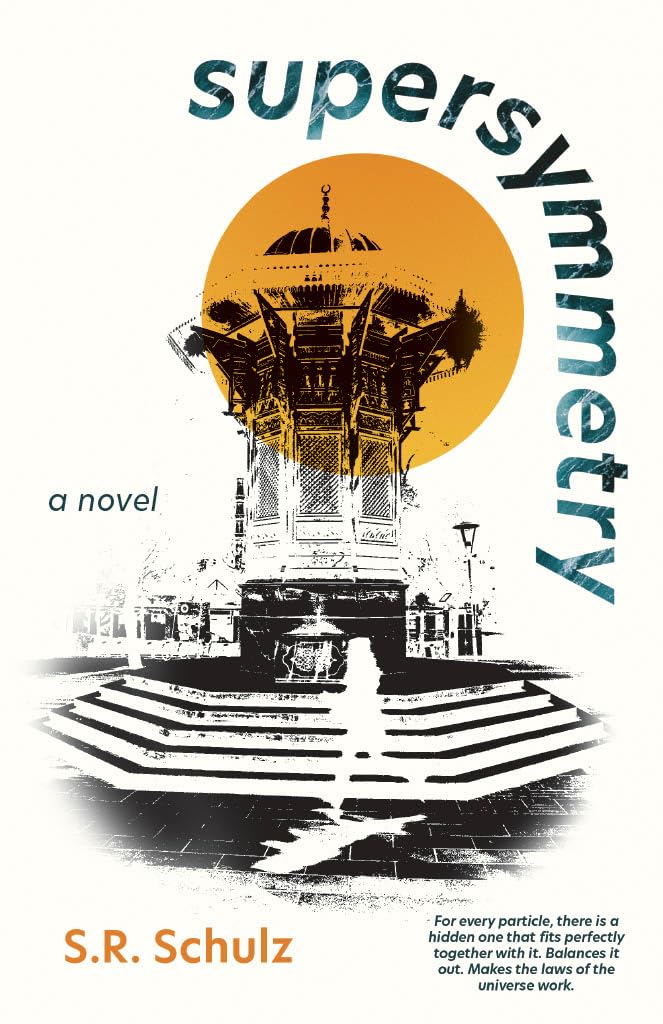

Penance plays into this message, and punishment of the generational sort breathes heavily throughout S.R. Schulz’s Supersymmetry. Later in the book, Lisa asks Luka whether or not he believes sin exists—he doesn’t—and they stumble over their spiritual augury, causing me to wonder what sins—besides violence and youthful intemperance—shuffled this young man so thoroughly into agnosticism. Trauma, likely; Lisa stirs her coffee and waits for a better answer, but none follow.

Supersymmetry’s emotional makeup is complex. On the one hand, we have a story about a reluctant young mother who feels cheated by life. Midway through the novel, her son is diagnosed with Autism, leading Lisa through such a forceful devastation that she temporarily renounces motherhood and her life in Oregon. Instead of university, she works a series of blue collar jobs, with very little in the way of a healthy support system. No loving partner to speak of, but instead, a man so immersed in ego and banality that he hardly registers her multifaceted approach to survival; if he had noticed, he could’ve saved her for a time. This brings me to Lisa’s mother, the character I found myself the most concerned with. Considering her history of substance abuse and (from what the novel hedges) a mental health condition left purposefully unidentified and exclusively self-medicated, she, in large part, is unfit for her role as backbone of Lisa’s household. A watery personality at best, Cathy displays instances of good humor and a quickness I suspect may be reticent of undiagnosed Bipolar. Cathy’s reliance on pills, at times, feels like absurdism, though it isn’t, and succeeds mightily at portraying the realistic excess of compulsive drug dependence, its effects on other areas of life, how it bends intelligence in a bow and replaces the semblance of a social life for one spent cushioned—propped by hourly highs—safely at home. I liked Cathy; she reminded me of how charming damage can look like, how those vulnerable persons (and in this instance, an entire family’s worth) necessitate protection, the kind that can only be afforded by the state. Due to Lisa and Cathy’s socioeconomic status, they’re given none; thankfully, this isn’t the case for Lisa’s son—there’s hope, private medicine’s intervention, and guidance sought early on.

In one respect, you could categorize Supersymmetry as a novel marked by an extreme manifestation of generational trauma. I call it generational ‘inheritance’, sometimes generational ‘curse’, “the sins of the father…”, or so to speak, and there’s much to be said for Schulz’s exclusive talent, too—he juggles birds-eye and intimate third—creating something fully-realized and with enough heart to influence the sympathies of even the most jaded and dry reader. Pain’s palpable; we have no other choice but to react to it. How Schulz candidly narrows the narrative to a point-of-view that initiates something like real intimacy speaks to his gift at storytelling and relaying realism palatably on the page. Readers begin to feel like appendages of this family, which further underscores the author’s skill at concocting absorbing scenes and dialogue that registers as innate. Obviously, Schulz knew his duty towards intimacy when he set out, that it has to be this way for us—especially those of us unfamiliar with the way trauma competes in families—in order for readers to grasp the asphyxiative atmosphere of a family sunk to its knees. This quality, in large part, has to do with the strength of Lisa’s inner-monologue. She reminded me of a millennial—her interior verbosity is marked by self-questioning, self-pity, and affixed with some of that generation’s (understandably) trademark coping mechanisms. Scrolling as means of self-soothing; celebrating the construct of meaning—while chasing its sidekick, a temporary, nighttime-activated happiness—through the glut of canned alcoholic seltzers and the rogue shot taken in place of true confession; equating escapism with legitimized, substantive change.

Which, of course, deals directly with the crux of the novel: Lisa leaving twice.

Who she leaves speaks brilliantly of Schulz’s scaffolding. Lisa abandons her men: son, boyfriend, boyfriend for son. But the removal of self could dually be applied to location if you’re looking for clues to larger themes. Schulz creates a conversation about globalism that he lets the reader decide what to do with, and I appreciated that approach. It subverts the tidy ending and speaks to the vast way of living we have options to, and the marriage of cultures Schulz works so well into Lisa’s story. In Schulz’s approach towards writing her, he marries mental health writing with romance, and illustrates how the act of loving another breaks ground for self-love. Lisa chooses to leave in order to discover herself and shield her family from the necessary shrapnel that accompanies a coming-of-age journey. Throughout the novel, she sins continually, and we forgive her immediately; she is met with the extravagance of special circumstances at nearly every turn, and that places a compromising rarity on her shoulders.

Lisa, archetypical of a wild thing, regretful of purposefully misplacing herself. Lisa as you, 17 years ago, or your daughter in five.

Lisa is everywhere, but fears everything; longs to waylay real connection, stay ‘between worlds’, tucked in the aircraft, for a few hours—untouchable. I’d hazard a guess we’re reading about a young woman suffering from some combination of C-PTSD and an undiagnosed mood disorder; her actions, then, shouldn’t be met with condemnation, but tolerance. Her character begs our concern. Let’s give it to her.